Every application has one goal: to help the users achieve a concrete goal, and in a seamless and pleasant way at that. That definition is as general as it gets but there’s a point to this vagueness.

And this point is: most often this is all you know when you start developing or expanding your software. You know you want to help the users. You may even know what exact activities the users should perform in your application. But do users really need this? And what do seamless and pleasant mean in this context? These questions are more difficult to answer.

Because here’s the thing: you can assume that the users DO need this feature, and you can assume how good user experience should look like. But assumptions most often backfire.

A minimum viable product (MVP) paves the way for the successful creation of many software products. A MVP lets you gauge the demand and test your idea without the risk of sinking significant resources into full development.

In this article, we share with you a brief guide about MVP and how to build a MVP that will help you success with your application

What Is a MVP?

A MVP is a version of your product, but with features pared down to reasonably minimal complexity, just enough to get initial customer feedback on which further development will depend. A MVP lets you validate your idea and tweak it so that it responds to the needs of your target audience as accurately as possible.

Remember, a well-developed MVP can’t be a buggy mess thrown together at the last possible instance—it should be a complete, usable piece of software. Think of it as a small apple tree (MVP) that you nurture and care for. In time, it gets better and bigger and yields crops that you can easily sell later.

A small and underdeveloped tree, on the other hand, will hardly bear sellable fruit. It’s the same with a MVP. You need to always aim for quality and functionality.

With an MVP available for early market release, you can gauge the real-life demand and acquire information as to the potential profitability before commissioning further development work.

Testing demand with an MVP is a proven method of alleviating the risk of substantial financial losses in case there is no user demand for the product. If there is demand, however, an MVP lets you start generating revenue and finance further product development.

As your target audience begins using your product, you can also start collecting insights about the strong and weak sides of the product. The direction of future development will be based on user feedback.

An MVP also facilitates building and expanding the user base as well as measuring product/market fit. You can use your audience’s unique set of preferences and behaviors to further tweak the product.

Prototype vs. MVP

Both a prototype and an MVP are ways to test your product with your target audience and show it to stakeholders. The difference between them is simple: a prototype is prepared earlier in the development process when you’re still exploring and expanding on your initial ideas – this could include creating paper, hand-drawn prototypes, or creating low-code simplified versions of your product with clickable UI elements.

An MVP is an already functional product that’s aimed at collecting feedback from initial users, with all the core features implemented and real UI designs rather than wireframes.

POC vs. MVP

With a POC vs an MVP, the distinction is even easier to spot. A Proof of Concept is a very schematic representation of your application or website which only tests if your product can be developed. It could be as simple as a list of core features with information about your resources allowing you to create them and the risks for each of these functionalities.

On the other hand, a Minimum Viable Product is further down the development process – it’s a working version of the product you work on that’s ready to get used by real-life users.

MVP vs. MMP

When you search for terms such as ‘MVP’ and ‘Minimum Viable Product’, there’s also another term that you’ll notice quickly: Minimum Marketable Product (MMP). In short, it’s a more advanced version of your Minimum Viable Product with the only difference being you’ve already found the product-market fit.

Why is a MVP Important?

Building a MVP has multiple perks.

#1. Funding

If you have limited resources for a full-fledged version of your product, creating a MVP can help your idea gain traction necessary to attract potential investors. Keep in mind, however, that it can be a double-edged sword – if your MVP is of poor quality, it might be tough to convince backers to part with their money.

#2. Tangible Feedback

Upon the release of your MVP, initial user feedback and interest will help you determine if your future product will raise enough steam to drive sales. You can then use the feedback to avoid pursuing wrong developmental avenues. You improve what works and drop what doesn’t.

#3. Reduced Costs

Before you dive headlong into the development of your product and commit all your resources to the project, a MVP lets you make a results-backed decision on the future profitability of your offer.

But the process of developing an MVP is pretty much the same as for any other piece of software – the difference is the number of features and their complexity. That’s where the reduction in cost lies and the relatively short time-to-market.

#4. Faster Deployment

Because a MVP is essentially groundwork for the end product, scaling up on top of this foundation brings down development time.

#5. User Acquisition

With a MVP out there, you can start expanding your target audience with early adopters who will also help further promote your application.

Is a MVP Necessary?

Theoretically, you don’t need a MVP to launch your product. But if you risk all resources on building a product with a complete set of features that later bombs on the market, the losses will be much greater than if you were to ease in with a MVP.

The rule of thumb is, if you have something new to offer via your product, a MVP is necessary because it will help you check if the idea takes off. When there’s little to no competition to your product, there’s really no other way to validate the product’s business offer other than through a MVP.

When to Build an MVP?

Theoretically, you don’t need an MVP to launch your product. But if you risk all resources on building a product with a complete set of features that later bombs on the market, the losses will be much greater than if you were to ease in with an MVP.

The rule of thumb is that if you have something new to offer via your product, an MVP is necessary because it will help you check if the idea takes off. When there’s little to no competition to your product, there’s really no other way to validate the product’s business offer other than through an MVP.

Another possible scenario where an MVP works well is an app or platform that packs an unfamiliar functionality. You wouldn’t want to go full-throttle on developing something that later won’t fly.

On the flip side, you can pass up on an MVP when what you’re building is already on the market—simply look to your competition to figure out what’s worth pursuing and then go after it. A POC, in this case, will be enough if you want to give your users an enhanced version of what’s offered by the competition.

An MVP also has the added benefit of being a finalized, albeit incomplete, product, which means the addition of new features can be iterated based on prior results and the available budget.

Are There Different MVP Types?

A MVP can take many forms. For example, Dropbox used an explanatory video showcasing what problem the software is intended to solve and how. The product video went viral among early adopters.

As per the Lean Startup framework, a MVP tests the business proposition of a product. So regardless of its form, it needs to be able to test the business value.

Minimum Viable Product Examples

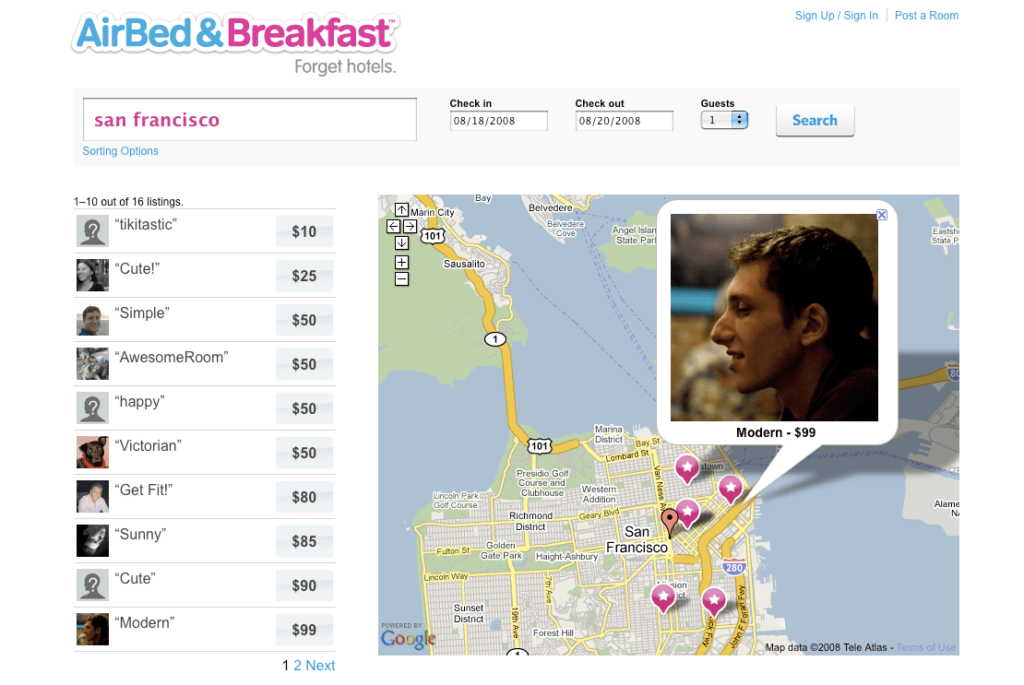

Airbnb is one of the most often cited MVPs that later turned into a billion-dollar app. In 2008, the company, back then going by the name AirBed&Breakfast, started as a simple booking website:

The website was enough to collect the necessary insight for further development and expansion.

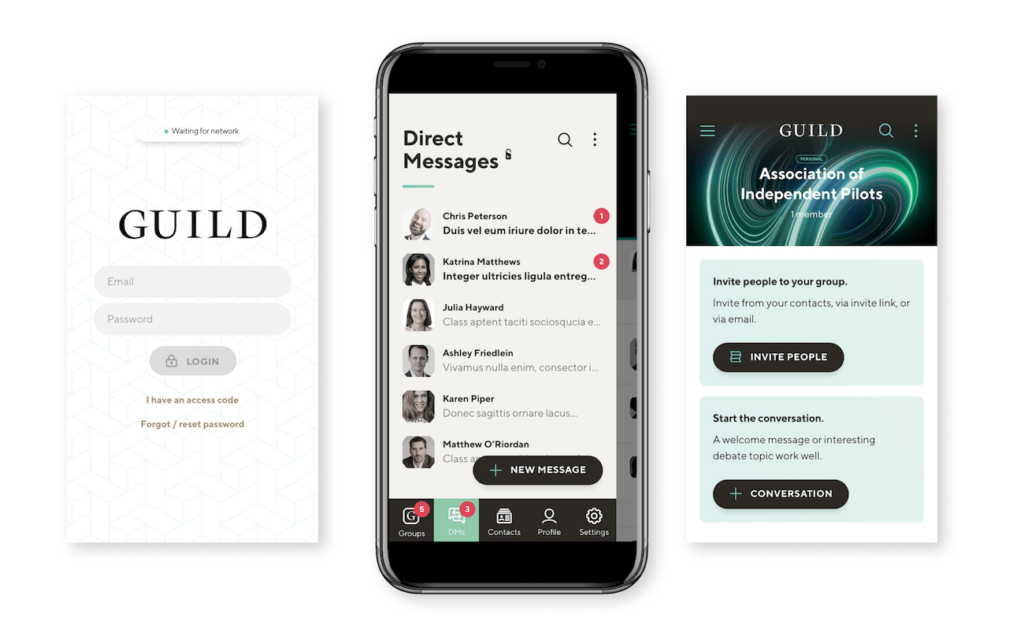

Another example of an MVP turned successful product is Guild, a messaging application that our teams helped build. The project started when the founders, who were already successful entrepreneurs, reached out to us with their initial concept and the need to test it quickly and securely.

With our support, they were able to release an MVP version of their app in July 2018 and then an alpha version 4 months ago. This move allowed them to collect $1.2M (£880.000) in seed funding in early 2019, and then further develop their product.

How “Minimum” Should an MVP Be?

A MVP should include only the high-priority features. But the product itself should be complete, meaning no low-quality graphics, glitchy UI, or functionality crashes. I can’t stress this enough, but sometimes it happens that, so caught up in moving quickly, product owners release an unfinished application, which is a sure way to turn potential customers away, even if the idea is great.

A good MVP needs to strike the perfect balance between:

- Functionality – the core features need to communicate value

- Design – no low-quality or temporary shortcuts here

- Reliability – no bugs ensured by extensive testing

- Usability- functionality and easy-to-use interface

How To Build A Value-Adding MVP

Eric Ries has written a book called Lean Startup that perfectly describes the thinking behind creating a value-adding MVP. There are a ton of great points and approaches worth adapting in business development.

So instead of recapping what the book has to offer, we’ll share our practical conclusions that come from over a decade of developing software.

When building software, there is a strong temptation to write down and plan every feature that comes to mind. MVP’s goal is to test a hypothesis but when the development gets going, it’s often the case that ideas for features accumulate. It’s quite a natural process but planning to chase after these ideas poses a couple of risks:

- The market can change and the ideas may stop being viable

- The funding can deplete before you get to something that the users will value

- It may turn out that the ideas didn’t pinpoint the users’ needs

And there are three ways to go about these risks here.

The Best Approach: Remember That You’re Experimenting

In this approach, you’re doing things by the book (and a very concrete one: Lean Startup). This means that you overcome the natural tendency to plan ahead, and focus on building a small app that will allow you to test things like:

- Do users really need what you thought they needed? Using Dropbox’s example: instead of building a cloud file-storage service, they started with a landing page that described what Dropbox would do, and placed an email subscription form there. This allowed them to test the idea cheaply and quickly.

- If the users need something slightly different from what you thought they needed, what exactly is it?

- What is the most efficient way to deliver what users need? How the product should behave for the best user experience?

You see how users react, and based on that you adjust. In short, MVP in this scenario is one interation of the build-measure-learn cycle.

You use as few assumptions as possible, you build an MVP, test everything with the users, and then adjust. Rinse and repeat.

Second-Best Approach: Develop The Crucial Features And Test

If for some reason you cannot approach the project as an experiment and you need to deliver a fixed idea, it’s best to identify just a couple of features (or even one) that are at the core of the idea. In other words: a feature without which the app couldn’t even exist.

Then you deliver this small and sometimes rough around the edges app to the first users and see how they react. You learn what they like, what else they need, what needs adjusting.

Third-Best Approach: Prioritize 20%, Deliver, Test

Some products are supposed to compete in an established market. In this scenario, the users are used to a certain way of doing things, and going against the current would be ill-advised. So naturally, there is already a set list of things a product should do and how it should work to ensure both differentiation and familiarity.

The best way here is to take the list of features and prioritize 20% of them. This will help to structurize the development process, and will still give some room for feedback from users. Because after they test the first version of the product, you can still adjust the planned features based on the users’ feedback.

How to Build a MVP?

Building a MVP can generally be broken down into four steps.

Step #1: Evaluate Your Idea and Narrow Your Target Audience

This is crucial in the journey toward building a successful MVP. So your first step is to make sure your product solves a real problem that plagues your potential customers. Many times startups fail because even though their idea is brilliant, it doesn’t solve a problem that demands attention.

Start by asking around what are the existing solutions to the problem your future product will be addressing. There are many ways to go about it: during networking, on LinkedIn, via simple online search. Be creative here.

Then analyze your target audience in relation to your product:

- Why would they use your product? Is there tangible value for them in it?

- Do you offer something that cuts down the time/resources/steps necessary to achieve something? What is the biggest pain point your product aims to solve?

- Are there groups of possible users to whom you could further adjust your offer and message? Can your product be used by different target audiences?

Step #2: Assess the Market for Competition

Assessing the market for competition will help you check how others approach solving the problem your product addresses, and maybe reveal areas where your offer can outperform others.

Checking the competition will also take care of some of the idea validation processes – if your competition is doing something you want your app to do, you’ll know the idea works. This will eliminate the need to validate the technical aspect of your assumption, hence no reason to build a proof of concept first.

If there’s no direct competition for your product, it can either mean your idea is innovative and can take the market by storm or that there’s no demand for the product. That’s why evaluating your idea and narrowing your target audience is so important.

How to assess your competition?

- Use tools that measure website traffic

- Check social media following and online mentions

- Read online reviews from their customers

Step #3: Define User Flow and Features

User flow is simply how your customers will achieve what they want via your app. For example, your app calculates a possible time in a marathon based on predefined user values. Split what’s necessary for the user to achieve the result into simple steps. The user opens the app -> inputs their values -> gets the result and optional training plans.

Next, you can start listing out the features of your MVP. Start with those most important, which means most closely connected to solving your customers’ problems—when figuring them out, try to take your customers’ perspective.

Now pick the one that directly addresses that problem. This is the foundation of your MVP. The remaining features will be incorporated in future iterations.

Note: You can also write down most features that come to your mind and tie them in with the user flow. But it’s not a necessity, as more features, especially the ancillary ones, will surface after you get feedback from early adopters.

Step #4: Build -> Measure -> Improve

The whole point of a MVP is to build a basic version of your product, measure how it fares on the market and among early adopters, and improve the product based on user feedback. You then do it again and again in a loop, building a better and more valuable product with every iteration.

Once the MVP is released, all data it generates is golden – make friends with data analytics.

Usage and traffic data will reveal your customers’ behaviours, demographics, and usability issues. Once you start filling your product with features, leveraging that information will help you make accurate, data-backed decisions.

Data can also help you monitor UX changes and check the viability of monetization strategies.

Optional Step #5: Pivot

If the feedback and data you’re receiving suggest there’s little interest in your product or the interest tapers off after users get familiar with your app, you need to prepare for some radical changes.

The pivot step requires you to reorganize the core of the MVP. There might be a need to repeat the development process from the start to offer the users the value the first MVP lacked.

While you can significantly decrease the need for a pivot by performing due diligence as outlined above, the risk is ingrained in startup development. To decrease the costs of pivot-related changes, make sure you’re developing the MVP in a technology that allows for rapid and agile changes.

Summary

When building an MVP, it’s paramount to think of it as a learning process – you release your MVP to learn more and more about the target audience to be able to serve it better with time and subsequent releases of your product.

If there was just one thing you could take out of this article, let it be this: MVP = experiment. Understandably, we don’t always have as much freedom to experiment as we would like, so you can adjust the MVP approach using what we’ve outlined above.

If you build your product with us, HuviTek can be sure of our professionalism and support in whatever you choose to do. If you have plan for any mvp development, please don’t hesitate to contact us for more support

- Message us

- Phone: +84 888 780 670

- Email: [email protected]

- Visit our website!

Flutter vs React Native for Mobile Development – Which is Better for Your App? – HuviTek

May 13, 2022[…] the development process, the MVP is an important step taken before the product becomes a full-fledged app. Such an approach offers […]

What is a Prototype? Benefits, Types, Examples and Tips – HuviTek

September 23, 2022[…] this part of my product design series about Proof of Concept, Prototype, and Minimum Viable Product, I’m discussing the former concept which can be very useful in deciding how your product should […]